Why I believe that Jesus is not God

This is a talk that I gave to the evening meeting at City of Edinburgh Methodist Church on Sunday 10 February 2013. The talk was accompanied by a slide show which does not add any further material.

Disclaimer: this is a talk, not an academic essay. It is not properly referenced according to the standards for an academic essay. It uses non‐original material freely without specific attribution, especially from Ted Whitten’s essay The Trinity – a Doctrine Overdue for Extinction (see Bibliography for a link), and from the Biblical Unitarian website.

Introduction

In this talk I will explain why I reject the doctrine that Jesus is God. The doctrine that Jesus is God is part of the Doctrine of the Trinity, and it follows that I reject the Doctrine of the Trinity.

Some reassurances

Before I go any further, I feel the need to give some reassurances.

First and foremost, I emphasize that I am not trying to take away from Jesus Christ any of the glory and position that God has given to him, or belittle in any way what he has done and continues to do for us, his church. I proclaim Jesus Christ as the Son of God. He made the ultimate sacrifice for all of us, and showed a greater love for us than any other human being ever has done or could do. He gave his life, so that we may have life eternal, and a clean slate with which to stand before God, free of sin. He is my saviour and my friend, and as I walk and talk with him today he continues to mediate between God and me, and fight on my behalf in life’s struggle. I confess Jesus Christ as the Son of God, but I do not believe that he is God, which is a different thing altogether.

Secondly, I acknowledge that some of you in this room – perhaps all of you in this room – accept the doctrine that Jesus is God. It is not my purpose to try to persuade you otherwise against your will. My aim is to show you that my own rejection of the doctrine is principled and reasonable, nothing more. If, on the other hand, you feel uneasy about the doctrine that Jesus is God and you have been running with it for many years only because you feel that, as a practising Methodist, you have no choice, then I hope to show you that, on the contrary, you have a choice.

Thirdly, most of you are aware that I teach in the Sunday school here at City of Edinburgh Methodist Church. I want to assure you that nothing controversial that I say this evening would ever pass my lips while I am working with the children and young people. As a Sunday‐school teacher I try to be orthodox.

My calling as a member of the Methodist Church

I have my Methodist membership ticket with me this evening. It sets out what I am called to do as a member of the Methodist Church.

- I am called to worship within the local church, including regular sharing in Holy Communion, and through personal prayer.

- I am called to learning and caring, through Bible study and meeting for fellowship, so that I may grow in faith, and support others in their discipleship.

- I am called to service, by being a good neighbour in the community, challenging injustice and using my resources to support the Church in its mission in the world.

- I am called to evangelism, through working out my faith in daily life and sharing Christ with others.

I take that calling seriously.

I am not called to accept Methodist doctrine. I can make no sense of the phrase “must believe”. I cannot choose what to believe: I believe what my mind, with input from the world around me, leads me to believe. I could never have become a Methodist local preacher, because Methodist local preachers are committed to accepting Methodist doctrine. I could never have been a member of a denomination such as Roman Catholicism whose members are expected to accept dogma. I am proud to belong to Methodism, a denomination which guides my beliefs but does not try to impose them.

The Methodist Quadrilateral

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, observes that our beliefs about God come from four sources: the Bible, tradition, reason and experience. These have become known as the “Methodist Quadrilateral” or the “Wesleyan Quadrilateral”. Primarily Methodists seek to discover the Word of God through reading the Bible. We are informed by tradition, which includes teachings like the creeds. We employ reason: God calls us to love him with all our mind as well as with all our heart, and this means using our own critical thinking to make sense of what the Bible says. And Methodism in particular has stressed the importance of our own life experience, especially when we have prayed and reflected about that experience with other Christians.

John Wesley insisted that the Bible is the first authority and contains the only measure by which all truth is tested. The Bible was delivered by authors who were divinely inspired. The Bible is sufficient of itself. It neither needs, nor is capable of, any further addition. I am not as sure as John Wesley was that the Bible contains the only measure by which all truth is tested, but I will not be challenging his assertion in this talk.

Methodist tradition, like the tradition of most mainstream denominations of the Christian Church, includes the doctrine of the Trinity. As a member of the Methodist Church, I do not lightly reject any doctrine taught by the Methodist Church. But within the Methodist Church I have freedom of belief, with responsibility: and after Bible study, fellowship and prayer it is my clear belief that, in the matter of the doctrine of the Trinity, tradition is outweighed by the Bible, by reason, and by experience.

What does the Doctrine of the Trinity say?

Figure 1 sets out the Doctrine of the Trinity in all its orthodoxy. This is the picture that emerged at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, and it has been the standard picture ever since in most branches of the Christian Church. There are two natures, or ways or kinds of being. The Greek root in the creeds translated as “nature” is οὐσία (ousia). There is divine nature, God, and there are three individual instances – the Greek word is ὑπόστασες (hypostases) – of that nature, namely God the Father, God the Son or Jesus Christ, and God the Holy Spirit. And there is human nature, humankind, and there are many billions of individual instances, humans, of that nature, namely you, me, countless others, and of course Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ belongs to both natures: he is fully human and fully divine. Technically he is called the hypostatic union of the two natures. That, then, is the orthodox position.

The billions of individual entities within the kind human are known as humans. That is how our language works. There are millions of individual animals of kind horse and each one is called a horse. There are millions of individual buildings of kind bungalow and each one is called a bungalow. However, the three individual instances supposed to be within the kind God are not to be called Gods. That would be three Gods. God is three, we are told, but there is one God. God is the class name, but we decline to use it as a count noun for the individuals. Now declining to use the class name as a count noun for the individuals runs counter to the normal usage of all known natural languages. It is an ad‐hoc linguistic device introduced by Trinitarians in an attempt to reconcile their view that there are three individuals who are God with the fundamental Judeo‑Christian truth that there is one God.

Three individuals are God, but there is one God. Is that reasonable? It seems to me that before I could believe in the Trinity I should have to lay aside my logic, my verbal reasoning. This I cannot do. Would it not seem rather out of character for God to expect his children to do this? Let me be clear here. I’m certainly not saying that everything spiritual has to be within human understanding. But when someone tells me I need to “accept the Trinity” (or anything else) “on faith”, my first response is “accept it from whom on faith?” For unless God tells us something in his Word, there’s no sense wasting mental energy trying to conceive of the inconceivable. And as I believe you’ll see, God does not tell us that three individuals are he.

What the Bible says

Let us look, then, at what the Bible says.

John 7:16

Jesus replied, ‘The teaching that I give is not my own; it is the teaching of him who sent me.’

Does this sound like God talking?

If Jesus was God, then it was his own teaching.

Jesus did not originate the doctrine he taught. It came from someone else, someone that he was not – God.

John 5:30

[Jesus replied,] ‘I cannot act by myself; I judge as I am bidden, and my verdict is just, because my aim is not my own will, but the will of him who sent me.’

Does this sound like God talking?

If Jesus was God, then he was doing his own will.

Matthew 26:39

He went on a little, fell on his face in prayer, and said, “My father, if it is possible, let this cup pass me by. Yet not as I will, but as thou wilt.”

Does this sound like God talking?

How many wills do we see here? Two.

Trinitarians also see two wills in these verses, but their interpretation of the two wills is at variance with what Jesus said. Trinitarians hold that Jesus himself had two wills, a human will and a divine will, with his human will following and not opposing his divine will. But on the contrary, Jesus does not say that he has two wills: he says that he has a will, and that God has a will. He contrasts his will with God’s will. He distinguishes himself from God.

Mark 10:17–18

Jesus said to him, ‘Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone.’

Surely here Jesus is not merely hinting that he is not God: he is being emphatic about it.

These examples could be multiplied twentyfold. Throughout his ministry, Jesus was at pains to distinguish himself from God. And the phrase “God the Son” does not appear anywhere in the Bible. Not once.

The Doctrine of the Trinity, in fact, does not appear anywhere in the Bible. Yes, it is possible, if you want, to read the Doctrine of the Trinity into the Bible in certain places, which we will be looking at shortly. You can read it into the Bible. But you cannot read it out of the Bible. Most of the world’s leading biblical scholars consider that Jesus himself did not believe that he was God. The Doctrine of the Trinity was constructed many years after the time of Jesus. It did not reach its final form, in which we know it today, until the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, some 420 years after the end of Jesus’s earthly ministry. Are we to suppose that 5th‑century churchmen had a greater understanding of God than Jesus had?

The Doctrine of the Trinity was forced on Christians. For over 1500 years it was often enforced at the point of a sword. The last execution in the British Isles for the blasphemy of denying the Doctrine of the Trinity was the hanging of a 20‑year‐old student, Thomas Aikenhead, in Edinburgh in 1697. One witness said of Aikenhead’s death:

[T]he preachers who were the poor boy’s murderers crowded round him at the gallows, and… insulted heaven with prayers more blasphemous than anything he had uttered.

It continued to be a criminal offence in this country to deny the Trinity until 1813.

Errors, mistranslations and forgeries

Over the hundreds of years following Jesus’s earthly ministry, the Bible accumulated a number of errors, mistranslations and forgeries, which appeared to support the Trinitarian standpoint. Let us look at two of the most blatant ones.

1 John 5:7–8 – The Johannine Comma

We read in the King James Version (KJV):

For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.

By contrast the New English Bible (NEB) simply says:

For there are three witnesses: the Spirit, the water and the blood, and these three are in agreement.

From the context it is clear that what is being borne record to, what is being witnessed to, is that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.

The extra words originated as a Trinitarian commentary note, and were added to some Latin manuscripts during the middle ages. They do not appear in any Greek manuscripts until the late middle ages. They are omitted from all reputable modern translations.

Matthew 28:19 – the Great Commission

We read in the New English Bible:

[Jesus said,] ‘Go forth therefore and make all nations my disciples; baptize men everywhere in the name

of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.’

Did Christ really instruct his disciples to baptize using this Trinitarian formula, “in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit”? It seems terribly unlikely, for if he did, the disciples cannot have been listening very carefully to their teacher. The book of Acts records several baptisms done in the early church, and they were consistently done, time and again, in the name of Jesus Christ.

The Trinitarian formula is in some but not all of the earliest Greek texts. It probably derives from early Christian worship. It is unlikely, though just possible, that it is what the author of Matthew’s Gospel wrote. But modern scholarly consensus is that it is not what Jesus said.

Trinitarian texts

Now there are, of course, many texts that Trinitarians use to support their doctrine which are not errors, mistranslations or forgeries. Let us look at some of those.

John 1:1–3, 14a

Here is a much‐loved text, central to the New Testament, that Trinitarians use: the opening of John’s Gospel. This translation is New English Bible:

When all things began, the Word already was. The Word dwelt with God, and what God was, the Word was. The Word, then, was with God at the beginning, and through him all things came to be; no single thing was created without him.

And in Verse 14:

So the Word became flesh; he came to dwell among us.

Trinitarians tell us that by the Word, John means Christ. According to them, this text is telling us that Christ existed in the beginning with God, and that Christ was God.

But not so fast! Let us look more carefully at what this text actually says.

John says, “When all things began, the Word already was.” He says “the Word”: he does not say “Christ”. And there is no reason to suppose that he meant “Christ”.

The New Testament of course was written in Greek. “When all things began,” says John, “the λόγος (logos) already was.” So what is this λόγος? The Greek word λόγος has a rich tapestry of associations. There is no single English word corresponding closely to λόγος. It may be translated ‘word’, but it may equally well be translated ‘principle’, ‘meaning’, ‘value’, ‘creativity’, ‘expression’, ‘thought’, ‘plan’, ‘purpose’, ‘reason’ or ‘wisdom’. Now if we understand that the λόγος is God’s creative self‐expression – his plan, purpose, reason and wisdom – it is clear to me that these things were indeed with Him in the beginning. And it is equally clear to me that God’s plan, purpose, reason and wisdom found their expression supremely in Jesus of Nazareth.

Most translations of John 1:1 give ‘Word’ an upper‐case ⟨W⟩. Does this mean John was saying the λόγος is a person?

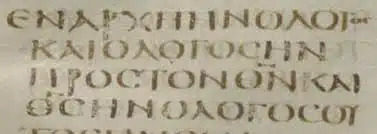

Figure 2 shows the opening words of John’s Gospel as they appear in the Codex Sinaiticus, a 4th‑century Greek manuscript. You can see that, as is invariably the case for early Greek manuscripts, they are written in an uncial script, and there is no distinction between upper‐case and lower‐case letters. Whether to translate λόγος into English as ‘Word’ with an upper‐case ⟨W⟩ or ‘word’ with a lower‐case ⟨w⟩ is a decision for the translator. Most English translations use an upper‐case ⟨W⟩, because the translators were working within a Trinitarian tradition, in which the λόγος was regarded as a person. The upper‐case ⟨W⟩ in the New English Bible is evidence of that Trinitarian tradition. It cannot be used as evidence of what John meant.

Most translations of John 1 use the masculine pronouns ‘he’ and ‘him’ to refer to the λόγος. “No single thing was created without him.” “He came to dwell among us.” Does that mean John was saying the λόγος is a person?

Greek nouns have a gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. We have already seen the words:

“The teaching that I give you is not my own: it is the teaching of him who sent me.”[Note 1]

Now the Greek word translated as ‘teaching’, διδαχή (didachē), is feminine. But in English we don’t say, “she is the teaching of him who sent me”; we say “it is the teaching of him who sent me”. English nouns have no gender. The translator will use the English neuter pronoun ‘it’ for a thing, and a masculine or feminine pronoun for a male or female person, regardless of the gender of the noun in Greek. Most English translations use masculine pronouns for the λόγος, because the translators were working within a Trinitarian tradition, in which the λόγος was regarded as a person (and a male person into the bargain). The masculine English pronouns in the New English Bible are evidence of that Trinitarian tradition. They cannot be used as evidence of what John meant.

Some translations of John 1 say, “The Word was God.” Does that mean John was saying the λόγος is a person?

“The Word was God” is a valid translation, but it needs careful interpretation. The Greek does not mean that the λόγος is to be identified with God. To say that the λόγος is to be identified with God would need the definite article in Greek: “The λόγος was ὁ θεός” (ho theos). But the Greek omits the definite article and says instead “The λόγος was θεός.” That means that God is the class to which the λόγος belonged, or that the λόγος had the attributes of God, or that the λόγος was divine. The New English Bible carefully expresses this by saying not “The Word was God,” but “What God was, the Word was.”

The opening of John reveals a deep truth in a beautiful way: “In the beginning there was one God, who had reason, a purpose, a plan, which was, by its very nature and origin, divine. It was through and on account of this reason, plan and purpose that everything was made. Nothing was made outside its scope. Then, this plan became flesh in the person of Jesus Christ and lived among us.” Understanding the opening of John this way fits with the whole of Scripture and is entirely acceptable from a translation standpoint.

John 20:28

Let’s now turn to another place in John’s Gospel which Trinitarians use as evidence that Jesus is God:

A week later his [Jesus’s] disciples were again in the room, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them, saying, ‘Peace be with you!’ Then he said to Thomas, ‘Reach your finger here: see my hands; reach your hand here and put it into my side; be unbelieving no longer, but believe.’ Thomas said, ‘My Lord and my God!’[Note 2]

Now Thomas of course did not say that in English. Nor did he say it in Greek. He most likely said it in Aramaic, a Semitic language, the common language of Palestine at the time. Now in the culture of the time, the Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek words that we translate as God or god were used with a broader meaning than we use the words God and god today. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew word אֱלֹהִים (elohim) “god” or “gods” is used of Moses[Note 3], it is used of the angel with whom Jacob wrestled[Note 4], it is used of King David[Note 5], it is used of the spiritual leaders of Israel[Note 6], and it is used of various pagan deities[Note 7]. In the New Testament, the Greek word θεός (theos) “god” is used of the Roman Governor Herod [Note 8], and Paul even uses it of Satan[Note 9]. Generally in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek the words that we would translate as God or god could be used of any great authority, especially any representative of God.

In English we can indicate that the word God refers to the one true God by giving it an upper‐case ⟨G⟩. The New English Bible reports Thomas as saying “My Lord and my God!” with an upper‐case ⟨G⟩. But we have already seen that the ancient Greek manuscripts do not distinguish upper‐case and lower‐case letters. The upper‐case ⟨G⟩ in the New English Bible is evidence of the Trinitarian tradition of the translators. It cannot be used as evidence of what Thomas meant, or what John had in mind when reporting what Thomas said.

Even Trinitarian scholars, by and large, do not claim that Thomas was identifying the risen Christ with the one true God. They appreciate that that would be too much for the existing knowledge of the disciples, and that the doctrine that the risen Christ is the one true God arose much later.

The context of the verse is that Jesus was alive. Thomas was astonished to see the risen Christ. Given the standard use, in the culture of the time, of words that we would translate as god to mean one with God’s authority, it certainly makes sense that Thomas would proclaim, “My lord and my god.” He was not birthing a new theology. He was proclaiming that the man Jesus, who had died, was risen and had divine authority.

Jesus did not complain about being called a god, because calling him a god fitted with the culture of the time. But he was absolutely clear that he is not the one true God, or as we would put it, God with an upper‐case ⟨G⟩. According to John’s Gospel, Jesus addresses his heavenly Father with the words:

“Eternal life is to know you, the only true God, and to know Jesus Christ, the one you sent.”[Note 10]

He is saying, quite explicitly, that only his heavenly Father is the one true God.

John 8:58

Here is another so‐called Trinitarian verse. It is from John’s Gospel, chapter 8, verse 58. This translation is New English Bible:

Jesus said, ‘In very truth I tell you, before Abraham was born, I am.’

There is a traditional Trinitarian interpretation of those words. The tradition is that Jesus is revisiting the words of God to Moses on Mount Sinai:

God said to Moses, “I am who I am”. He said further, “Thus you shall say to the Israelites, ‘I am has sent me to you.’”[Note 11]

Thus, the tradition goes, by these words Jesus is claiming to be God. The idea is that if Jesus had said “I am something or other”, such as “I am from Nazareth” or “I am 33 years old” then his words would have been unexceptional, but that the use of the words “I am” on their own, without any complement, revisit the words of God on Mount Sinai.

Many modern scholars question this. There are several reasons why it does not seem quite right.

Firstly, the Greek words translated as “I am”, ἐγώ εἰμί (egō eimi) were very commonly found without any complement in Greek literature and indeed are commonly found without any complement in the New Testament. They may be translated “I am the person”, or “I am he”, or “It is I”. For example in John Chapter 9 the bystanders are debating whether the man standing in front of them really is the man who was born blind, and the man says to them ἐγώ εἰμί, “I am he”. He is not claiming to be God.

Secondly, the Hebrew words attributed to God on Mount Sinai, אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה (ehyeh asher ehyeh), translated as “I am who I am”, are really quite different from the Greek words ἐγώ εἰμί. The Hebrew words mean something like “I will prove to be whatever I will prove to be.” And the verb does have a complement. It seems very strained to argue, as Trinitarians do, that Jesus’s words ἐγώ εἰμί should be read as a revisiting of ehyeh asher ehyeh because they have no complement, when in fact ehyeh asher ehyeh does have a complement.

So it seems that the claimed link between Jesus’s words and God’s words on Mount Sinai evaporates. Jesus is not claiming to be God.

It is clear that Jesus’s words, “Before Abraham was born, I am” are claiming a certain timelessness. But a careful reading of the context of the verse shows that Jesus was speaking of “existing” in God’s foreknowledge. In the context of God’s plan existing from the beginning, Christ certainly was “before” Abraham. Christ was the plan of God for man’s redemption long before Abraham lived.

John 10:30

Here is another verse that is sometimes claimed to identify Jesus with God:

[Jesus answered,] The Father and I are one.[Note 12]

To say that two things are one is a very common turn of phrase, both in modern English and in Biblical Greek. It simply means that they are one in purpose.

When a minister marries a couple and tells them, “Now you two are one”, nobody takes the words to mean that the husband and the wife are the same being.

In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul says:

I have planted, Apollos watered; but God gave the increase. So then neither is he that planteth any thing, neither he that watereth; but God that giveth the increase. Now he that planteth and he that watereth are one.[Note 13]

Nobody takes these words to mean that Paul and Apollos are the same being.

In John’s Gospel Jesus prays:

Holy Father, protect by the power of thy name those whom thou hast given me, that they may be one, as we are one.[Note 14]

Nobody takes these words to mean that all Christians are the same being.

It is abundantly clear that when Jesus says “My father and I are one” he means that they are one in purpose, or united in their goals. To argue that the verse is a claim by Jesus to be God would be quite absurd and would display complete ignorance of basic interpretive method.

Mark 2:5–7

In Mark’s Gospel we read the following:

When Jesus saw their faith, he said to the paralysed man, ‘My son, your sins are forgiven.’

Now there were some lawyers sitting there and they thought to themselves, ‘Why does the fellow talk like that? Who but God alone can forgive sins?’[Note 15]

On several occasions Jesus told the Pharisees that their doctrine was wrong. Here we have an instance. There is no verse of Holy Scripture that says, “Only God can forgive sins.” That idea came from the Pharisees’ tradition. The truth is that God grants the authority to forgive sins as he chooses. He granted that authority to the Son and, through the Son, to the apostles. John 20:23 records Jesus saying to them: “If you forgive anyone his sins, they are forgiven.”

Some Trinitarians argue that since Jesus claimed to forgive sins he must be claiming to be God. Equally they argue that since Jesus in fact forgave sins he must in fact be God. If that was valid reasoning, then it would be equally valid reasoning to say that since the apostles forgave sins, they must be God. They weren’t.

Worship

We sometimes hear the Trinitarian argument that:

- worship is due to God alone;

- the New Testament says that worship is due to Christ;

- therefore Christ is God.

That argument is based on a confusion of two separate Greek verbs. In the New Testament there are two separate Greek verbs that may be translated as ‘worship’. There is προσκυνέω (proskuneō) which means to do homage, by words or by kissing the hand or by bowing down. It derives from a word that is used of a dog licking its master’s hand. And there is λατρεύω (latreuō), which means to render sacred service. Now, worship in the προσκυνέω sense can be offered to anyone. In the New Testament we read of worship in the προσκυνέω sense being offered to God, to other heavenly beings, to Jesus, to earthly kings, to the Jewish High Priests, and even to demons. προσκυνέω is what tennis players at Wimbledon did until recently towards the Royal Box! By contrast worship in the λατρεύω sense can properly be offered only to God, as Jesus reminded the devil in the wilderness.[Note 16]

In the New Testament there are 21 occurrences of the verb λατρεύω. In 18 of these, the object of worship is God. In a further two, the object of worship is a person other than God and the context makes it clear that such worship is considered improper. That leaves one ambiguous verse, in which it is not clear whether the object of worship is God, or Jesus. The verse is in Revelation, and it reads:

The throne of God and of the Lamb will be there, and his servants shall worship (λατρεύω) him.[Note 17]

The Greek syntax is such that the pronoun translated as him may refer either to God or to the Lamb (who, uncontroversially, is Jesus).[Note 18] The pronoun is singular: it cannot refer to both. Trinitarians and non‐Trinitarians argue furiously over which is meant.

For myself, I am happy to read the pronoun as referring to God and not the Lamb. We know that worship in the λατρεύω sense can properly be offered only to God. Why complicate the issue by unnecessarily introducing a problematic and controversial interpretation? It is better to take the interpretation that accords with the New Testament as a whole.

Miracles

Occasionally we hear Jesus’s miracles put forward as evidence that he is God. There is absolutely no merit in such an argument. Moses, Joshua, Elijah and Elisha performed miracles. Jesus’s apostles performed miracles. Before a person can be canonized by the Roman Catholic Church, he or she must be confirmed as having performed two miracles. In every case, miracles are worked by the power of God acting through the human being. The greatest miracle of all time is the Resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. Jesus did not rise of his own accord. God raised him.

Summary

Let me now summarize.

Throughout the New Testament, Jesus presents as a man who obeyed God, prayed to God, worshipped God, sought guidance from God.

There are very, very few explicitly Trinitarian texts in the New Testament: and modern scholarly consensus is that those that there are do not accurately reflect what Jesus said.

The phrase “God the Son” appears nowhere in the Bible.

All of the so‐called “Trinitarian texts” can easily bear alternative interpretations that are non‐Trinitarian. It is better to adopt non‐Trinitarian interpretations so that they harmonize with Holy Scripture as a whole.

Trinitarianism does not come from the Bible: it emerged after the last books of the Bible were written, it was set in stone by worldly ecclesiastical powers some hundreds of years after Jesus, and it was forced on Christians at the point of the sword.

Trinitarianism, with its assertion that three individuals are God while there is one God, is illogical, unless we adopt the ad‐hoc linguistic device of declining to use the class name God as a count noun for the individuals that are asserted to be God. I am not prepared to adopt that device, as that would mean abandoning my own λόγος – my logic, my reasoning, as mediated by, and expressed in, the words of my native language.

Jesus Christ is my Lord and Master, my Saviour, my teacher, my friend. He gave his life, so that I may have life eternal, and a clean slate with which to stand before God, free of sin. He mediates between God and me. I proclaim him the Son of God. He is not God.

References

- John 7:16, NEB

- John 20:26–28, NEB

- Exodus 7:1 KJV: And the Lord said unto Moses, See, I have made thee a god (elohim) to Pharaoh.

- Genesis 32:28 NRSV: “You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God (elohim) and with humans, and have prevailed.”

- Psalm 45:6 NRSV: Your throne, O God (elohim) endures forever and ever.

- Psalm 82:6 NRSV:

I say, “You are gods (elohim),

children of the Most High, all of you;

nevertheless, you shall die like mortals,

and fall like any prince.” - Amos 2:8 NRSV: in the house of their God (elohim) they drink wine

- Acts 12:22 NEB: Herod harangued them; and the populace shouted back, ‘It is a god (θεός) speaking, not a man!’

- 2 Corinthians 4:4, NEB: Their unbelieving minds are so blinded by the god (ὁ θεός) of this passing age

- John 17:3, Contemporary English Version

- Exodus 3:14, NRSV

- John 10:30, NRSV

- 1 Corinthians 3:6–8, KJV

- John 17:11, NEB

- Mark 2:5–7, NEB

- Luke 4:8 NRSV: Jesus said to him, “Away with you, Satan! for it is written, ‘Worship (προσκυνέω) the Lord your God, and serve (λατρεύω) only him.’”

- Revelation 22:3, NEB

- του θεοῦ ‘of God’ is masculine, του ἀρνίου ‘of the Lamb’ is neuter, and the pronoun αὐτῷ translated as him has the same form whether it is masculine or neuter.

Bibliography

My talk uses non‐original material freely from the following two sources without specific attribution.

Ted Whitten’s essay The Trinity – a Doctrine Overdue for Extinction

That essay is no longer on the Web where the author put it, but you can retrieve it at your own risk from Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. Here are Internet Archive’s Terms of Use.

Biblical Unitarian website

This is at biblicalunitarian.